How did the King of 20th Century Fashion Disappear into Oblivion?

They compared his legacy to Picasso’s and called him the “King of Fashion” in America and Le Magnifique in Paris. He liberated women from corsets, dominated Belle Epoque fashion with his lavish draped designs and was the first French couturier to commercialise his own perfumes, now an industry standard marketing concept. Paul Poiret should be a household name, but instead he died in poverty, his genius rejected, his leftover stock sold by the kilogram as rags.

Born in working class Paris to a cloth merchant, as a teenager, Paul Poiret apprenticed in an umbrella shop where he collected scraps of silk to fashion clothes for one of his sister’s dolls. Around this time he also began taking his fashion sketches to Louise Chéruit, one of the first women to control a major French fashion house. She purchased a dozen designs from him and before long, Poiret found himself working for the most prominent couturiers in Paris.

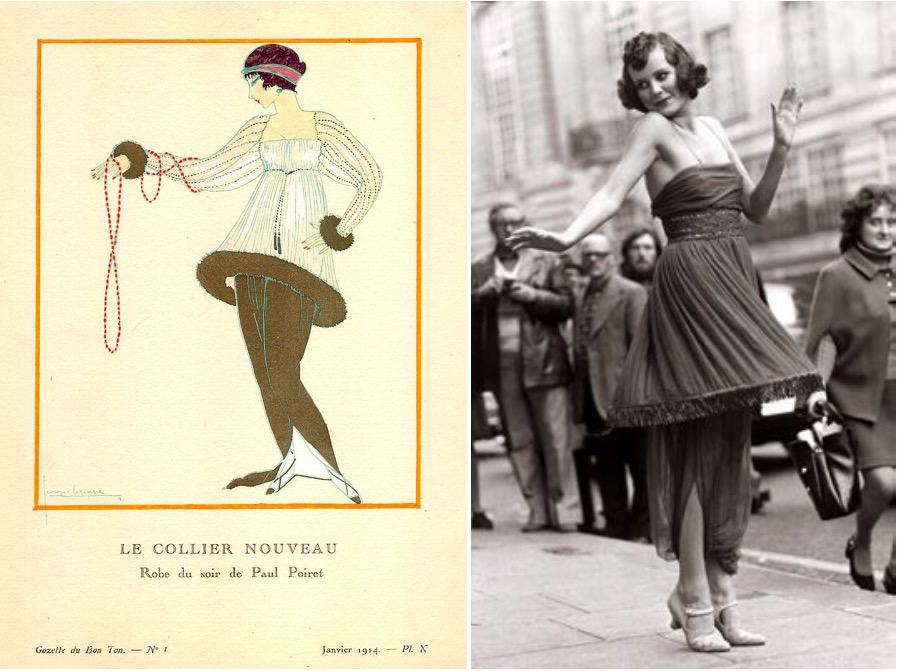

At the House of Worth, then the biggest fashion house in Europe, he was responsible for creating simple and practical garments, or what his superior called, “fried potatoes”; side dishes to Worth’s opulent ball gowns. But Poiret’s designs would quickly prove too unconventional and modern for the oldest and most revered of couture houses.

He was prompted to end his relationship with the company when he presented the Russian Princess Bariatinsky with a new coat cut like a kimono. “What a horror!” she said upon seeing the design. “When there are low fellows who run after our sledges and annoy us, we have their heads cut off, and we put them in sacks just like that.”

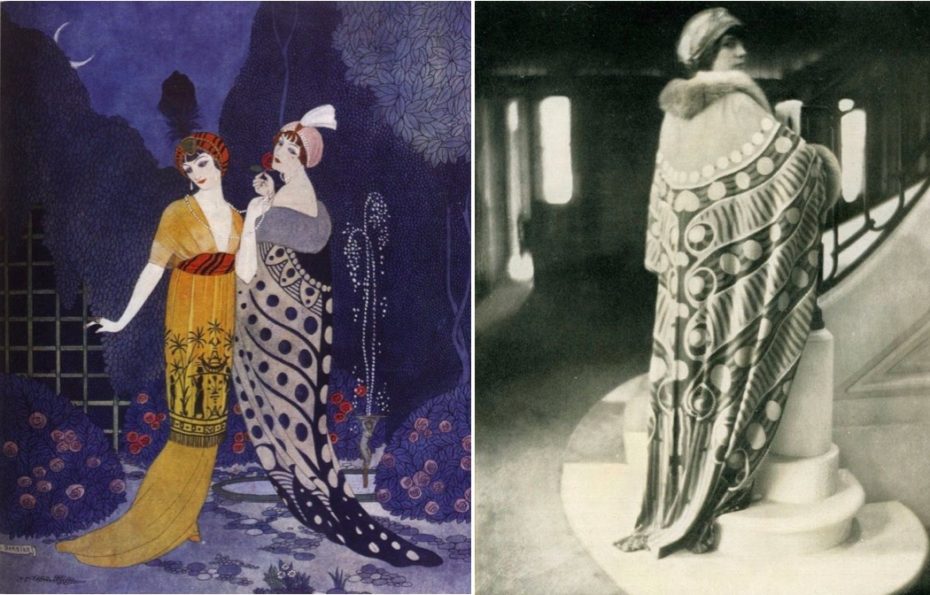

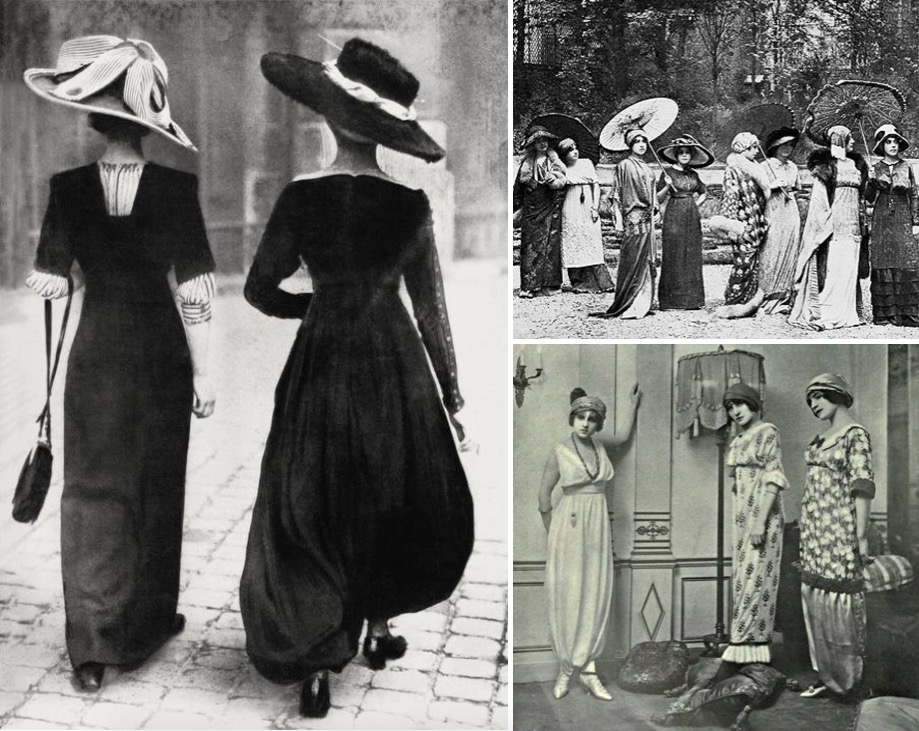

He didn’t take the Princess’ comments to heart and continued on his path to break with the established conventions of dressmaking. He began with the woman’s body, trapped in a corseted waistline since the Renaissance. He looked to Greek, Japanese and Middle Eastern silhouettes, shifting the emphasis away from strict tailoring and towards the art of drapery.

A revolution in dressmaking was on its way; the “S” silhouette (forward-projecting breasts and protruding bottoms) was out. Poiret wasn’t alone in starting the revolution. A handful of female designers were also advancing the uncorseted silhouette (you might remember the Belle Epoque Body-con Dress that was too Sexy for Paris), but it was Poiret who became most widely associated with the new look.

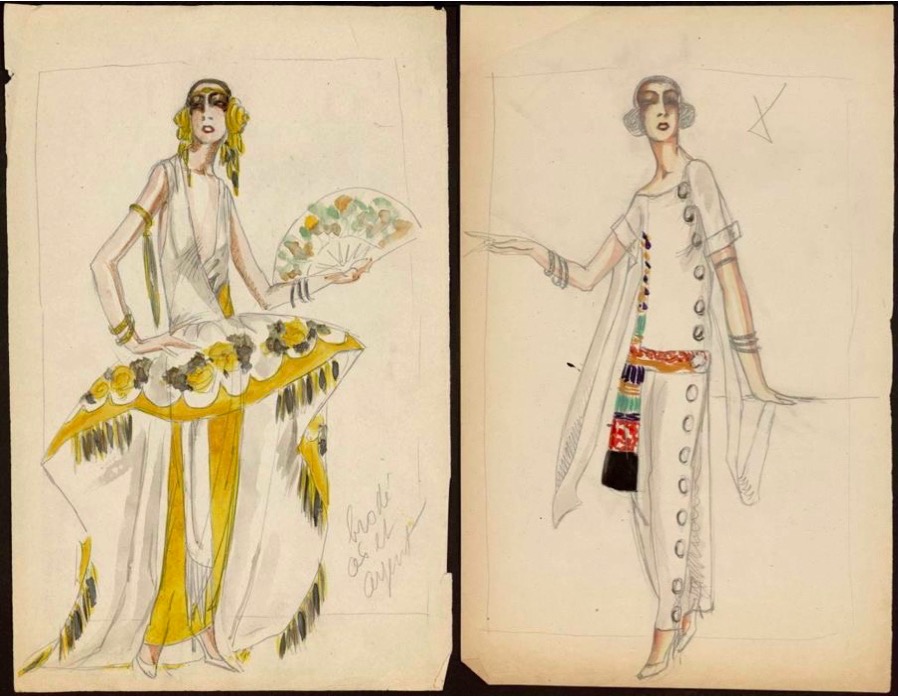

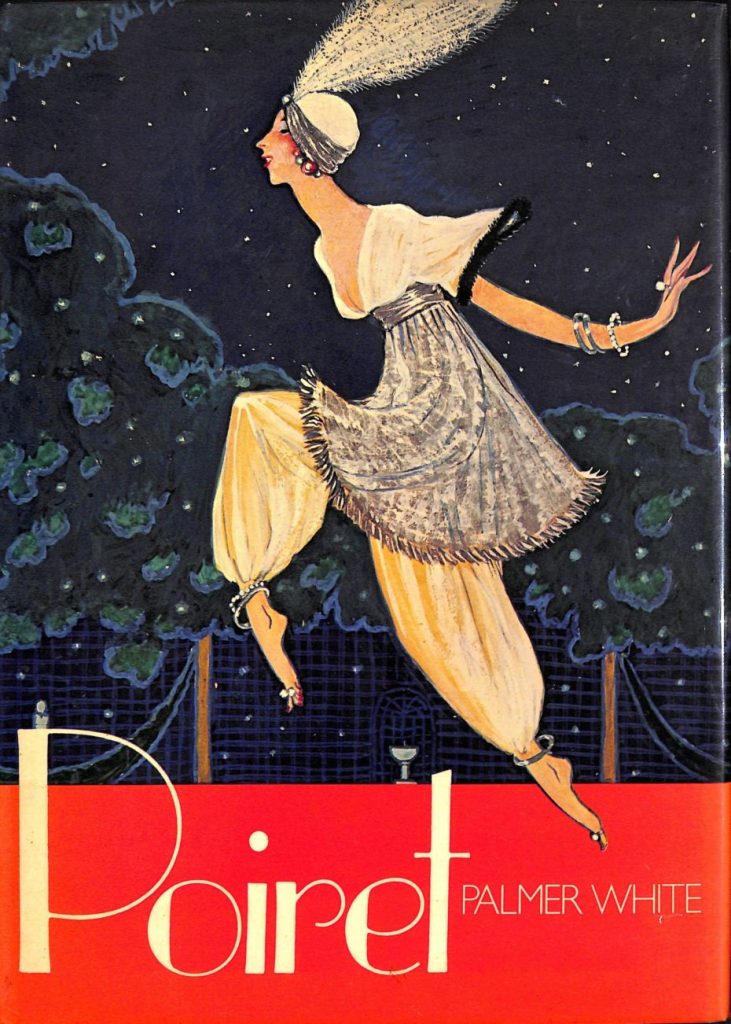

Other designs Poiret became most recognisable for was his cocoon coats, lampshade dresses, sultana skirts, harem pants, fringed capes and turban hats, all inspired by an expression of orientalism, a reference that you can often recognise in Yves Saint Laurent’s work from the 60s and 70s.

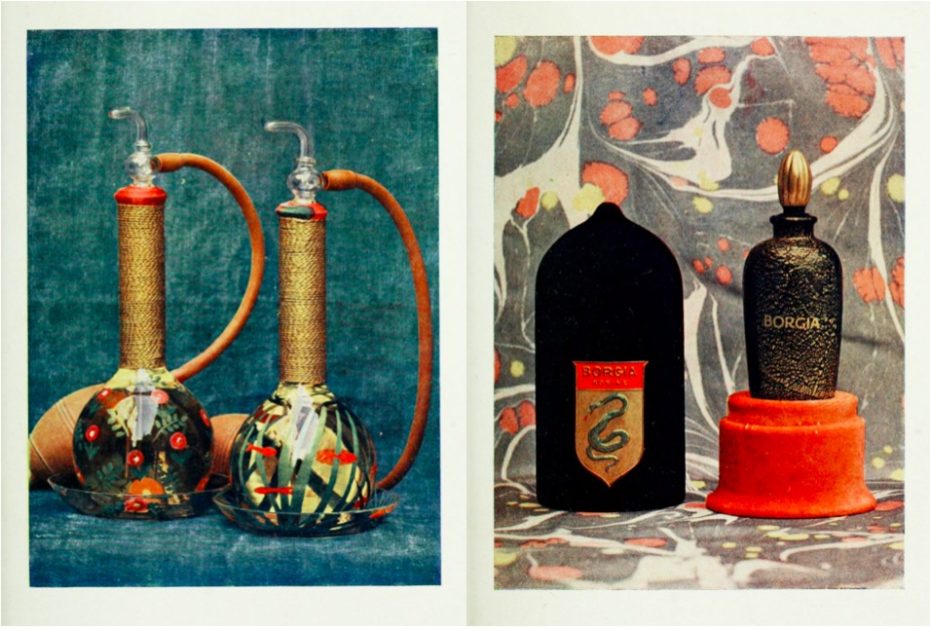

Poiret was also the first couturier to promote the concept of a “total lifestyle” brand, establishing his own cosmetic and fragrance company as well as an interior decorating business under the House of Poiret. Reigning supreme in Paris haute couture between 1903 and World War I, his instinct for marketing and branding was unmatched by any other Parisian designer.

When he unveiled his perfume brand, “Parfums de Rosine” (named after his daughter), he held a lavish fancy dress party for the cream of Parisian society that would keep them talking for months.

The event was known as “The Thousand and Second Night” and the gardens of his home were filled with lanterns, tents, and tropical birds.

Poiret himself dressed as a sultan and each of his guests took home his new perfume, “Persian Night”.

Designers has always used sketches to illustrate their designs, but Poiret was the first to use photography. An April 1911 issue of the magazine Art et Décoration is considered to contain the first ever modern fashion photograph shoot. In an attempt to promote fashion as fine art, photographer Edward Steichen chose to snap dresses by Poiret.

He was invited to show his designs at 10 Downing Street for the British Prime Minister and London’s elite. The Americans called him the “King of Fashion”; designer of choice to some of the brightest celebrity icons of the day such as Marchesa Luisa Casati and Joan Crawford.

But then the ugliest of mankind’s inventions took centre stage. World War I lured a proud Poiret from his fashion house to serve in the French army as a military tailor. By the time he returned, his business was on the verge of bankruptcy.

A certain Coco Chanel had arrived on the scene with her sleek and simple clothes that suited the post-war mood. Utility and function overruled luxurious and sensual. He was criticised for his “poorly manufactured clothes” and irrational construction. Unable to merge modernism with his own artistic vision, in the midst of a stock market crash he began losing support from his business partners and even his friends. A year before the closure of his business, after 23 years of marriage, he divorced his wife who he had once called “the inspiration for all my creations … the expression of all my ideals.” The far from amicable divorce sent him further into debt and after his fashion house closed, he was reduced to taking odd jobs as a street painter. Over the next 15 years before his death, his ground-breaking designs would be entirely forgotten, his couture house’s leftover stock sold by the kilogram as rags.

Penniless, he tried selling drawings to customers at Parisian cafés. Taking pity on the sorry state of their former colleague, the association of haute couture even discussed giving him a monthly allowance to keep him afloat, but the idea was rejected by his former employer, the House of Worth.

In the end, only two people helped Poiret from encountering complete ruin. A former employee, France Martano, fed him regularly at her family’s Parisian apartment to make sure he never went hungry. She showed him kindness when everyone else had forgotten him, even though years before, Poiret had erased her from his memoirs after she left him to become an independent couturier in Paris.

His other friend Elsa Schiaparelli, and greatest rival of Coco Chanel, paid for his burial and ensured his existing works would eventually find their way into the hands of collectors and museum archives.

The revival of the Poiret brand came in early 2013 when Chung Yoo-kyung, a grand-daughter of one of the Samsung founders and responsible for bringing many luxury brands such as Givenchy, Céline to South Korea, embarked on a journey to start a high-fashion house. In 2015, she acquired the Poiret trademark at auction for an undisclosed sum, including the fashion house’s archives. Designer Yiqing Yin and founder of a Paris-based couture label was been hired to design the new Poiret collection.